Racial Justice Through Tragic Optimism

The time between the conclusion of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month (AAPI Heritage Month) and the celebration of Juneteenth is a great opportunity to reflect on the complexities of racial justice. CFR Staff Psychiatrist Dr. Maura Dunfey shares how her experience raising biracial children, having a grandfather who fought the Japanese in World War II, and her understanding of post-traumatic growth to view racial justice through tragic optimism.

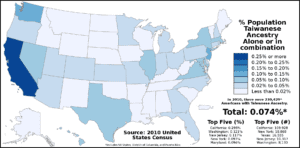

15,000 – 20,000 Chinese workers built the Transcontinental Railroad despite horrendous working conditions and ongoing racism.

Family Reflections and Racial Identity

Over the month of May, I took time to reflect on my husband’s Taiwanese heritage, our children’s biracial identity, and our unexpectedly intertwined family histories from 78 years ago. May is AAPI Heritage Month, which recognizes and honors the achievements and influences of Asian American and Pacific Islander Americans who have helped shape the culture and history of the United States.

In 1992, Congress established May as AAPI Heritage Month to coincide with two key milestones: the arrival of the nation’s first Japanese immigrants (May 7, 1843) and Chinese workers’ pivotal role in building the transcontinental railroad (completed, May 10, 1869). The move expanded what had been Asian/Pacific American Heritage Week since 1978. In 2021, a presidential proclamation expanded this to include Native Hawaiians.

The Okinawa Prefectural Peace Park (pictured here) is part of the Cornerstone of Peace in Itoman, Okinawa, Japan.

10,000 Miles and Back

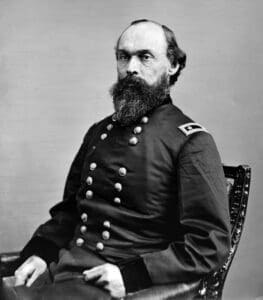

The end of AAPI Heritage Month coincided with Memorial Day, which provided an opportunity for further reflection. My grandfather was a 1st Lieutenant in the 6th Marine Division during WWII. He fought in Guam and in the Battle of Okinawa. He was wounded in a rice paddy where he lay for 6 hours waiting for it to be safe enough to evacuate. He had multiple surgeries overseas but was eventually able to make it home safely.

I have a vague memory of wanting to talk to my grandfather about what I perceived to be some type of prejudicial language with racial undertones. However, I can not remember specific details. I remember being advised to not have the conversation because my grandparents were a “different generation.” I often wonder what that conversation would have been like. I imagine it could have been an opportunity for deeper understanding and growth. By the time I came around, my grandfather had done years of soul searching, self-reflection, and reconciling with his past.

In 1987, my grandfather made the 10,000+ mile trip back to Okinawa, Japan with five to six dozen USMC 6th Division veterans for the dedication of a 25-foot high, granite statue in honor of fallen comrades, Japanese soldiers, and civilians. He noted that it was “the first time that any memorial has been put up in collaboration with the enemy… erected by both the US and Japanese veterans, who were once adversaries on the battlefield. It represents an epic moment in [World War II] history, standing proudly as a symbol of man’s ability to effect a reconciliation from even the most adverse conditions.”

My Grandfather May Have Been Ahead of His Time

30 years later, I’ve had relatives proudly declare that they’ve never thought of my children as biracial or my husband as Taiwanese American in spite of my politely asking and then pleading with them to do so. The same idea that they are a “different generation” is used as a reason for their ignorance. At the end of AAPI Heritage Month 2023 and in recognition of Memorial Day, it seems reasonable to emphatically state that being of a “different generation” is not a valid reason for bigotry, ignorance, hate, or intolerance.

My grandfather may have been ahead of his time. He found a way through personal tragedy to question the systemic forces of war, reconcile with enemies, and stay true to his democratic values – for which he had nearly lost his life. He did not perpetuate the hate, bigotry, and intolerance that he so easily could have. In 1981, he wrote: “After 37 years, I am still asking myself – why? Why did we fight, why did I ever meet these wonderful people who died so I could live? And why do we fight in the first place… There must be a better way, but we are not bright enough to see it.”

Viktor Emil Frankl (pictured here) was a Jewish-Austrian holocaust survivor and psychiatrist who founded logotherapy, a school of psychotherapy that describes a search for a life’s meaning as the central human motivational force.

Post-Traumatic Growth

I am reminded of two blogs by fellow Racial Equity Working Group colleagues from the past few years. Last year, Allen-Michael Lewis, MS, LMFT wrote, “Being able to shy away from conversations about racism and prejudice is a privilege that you may have that BIPOC [children] do not have.”

At the end of 2020, Dr. Bea Hollander-Goldfein, LMFT, wrote about the pandemic, “When researchers and clinicians look at who copes well in crisis and even grows through it, it is not those who push away and distract from their feelings; it’s not those who focus on pursuing happiness to feel better; it’s those who cultivate an attitude of tragic optimism.” The term was coined by Viktor Frankl, a Holocaust survivor, and psychiatrist from Vienna, who authored the 1946 book, Man’s Search for Meaning. Tragic optimism is defined as “the ability to maintain hope and find meaning in life, despite its inescapable pain, loss, and suffering.”

Dr. Hollander-Goldfein added to this definition the “undeniable reality that pain, loss, suffering, and difficulty are a part of life for all of us. It is also true that life is rich with the potential for meaning, joy, fulfillment, spiritual expression, and human connection.” She writes, “In general, resilient people have intensely negative reactions to trauma, just like those people who have a hard time coping. They experience despair and stress and acknowledge the horror of what’s happening like anybody else. But even in the darkest of places, they see glimmers of light, and this ultimately sustains them.”

“Even more than helping them cope, adopting the spirit of tragic optimism enables people actually to grow through adversity. We know that only a small percentage of people actually develop Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) after trauma, while, on average, from one-half to two-thirds of trauma survivors exhibit what is known as Post-Traumatic Growth. It’s not the adversity itself that leads to growth. It’s how people respond to it.”

Psychologists Dr. Richard Tedeschi and Dr. Lawrence Calhoun coined the term “Post-Traumatic Growth” in the 1990s. “The people who grow after a crisis spend a lot of time trying to make sense of what happened and understanding how it changed them.” In other words, they search for and find positive meaning.

On June 19, 1865, Union General Gordon Granger informed the African American citizens of Galveston, Texas that all slaves were emancipated months after the Civil War’s conclusion.

Racial Justice Through Tragic Optimism

I am grateful for the tragic optimism and post-traumatic growth that has been passed on to me by my parents, grandparents, and countless other family members. It is a daily source of strength for me and it fuels the responsibility we bear as allies to be proactive (not reactive), to show up early, to speak up and speak out, and to intervene when necessary. With glimmers of light, hope, and strength, I look ahead to the upcoming Juneteenth holiday, where we will honor Black Americans’ resilience, connection, and joy in the midst of ongoing adversity.

Dr. Maura Dunfey (pictured here) is a Staff Psychiatrist at Council for Relationships.

About the Author

Dr. Maura Dunfey is board certified in General Psychiatry and Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and has additional certification as a Child and Family Therapist. If you have questions about racial justice through tragic optimism, or if you are interested in a psychiatry appointment, click here to request an appointment.

You may reach Dr. Dunfey at mdunfey@councilforrelationships.org or 215-382-6680 ext. 7058.

See our Therapist & Psychiatrist Directory to find a different CFR therapist or psychiatrist near you.

About CFR’s Psychiatric Services

CFR Staff Psychiatrists are trained medical doctors who can evaluate whether medication would be helpful in a client’s treatment. They can prescribe medications and provide ongoing medication management. Staff Psychiatrists also provide psychotherapy, as do CFR’s staff therapists.

To learn more about CFR’s Psychiatric Services, and to request an appointment, click here.

More from CFR

“I Don’t See Color”: White Caregivers Raising BIPOC Children