Understanding Trauma: Poland & the Holocaust

Holocaust Remembrance Day, colloquially called Yom HaShoah in Israel, is an annual day of reflection and commemoration marking the date of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Bea Hollander-Goldfein, PhD, LMFT, is a Co-Director of CFR’s Transcending Trauma Project and a Staff Therapist. Here, Dr. Hollander-Goldfein, the child of a Holocaust survivor, shares her story of visiting Poland and navigating the complexity of learning to understand the trauma in not only her life but the lives of others.

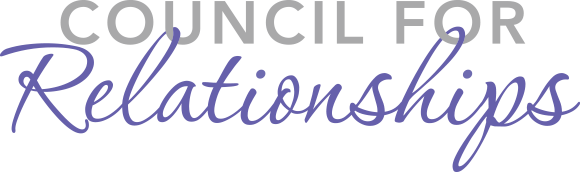

This map shows the locations of the Nazi Concentration Camps in both Germany and Poland, along with the different types of camps.

To rebuild a life in Poland amid the ongoing trauma of the Holocaust.

I went to Poland in 2016, but my mother would not have approved. My mother passed away in 2003. She came to the United States in 1949 as a refugee from Poland and survivor of the Nazi attempted genocide of European Jewry. My mother was a Holocaust survivor. She never talked about going back to Europe to see her hometown. She spoke of Poland as a land soaked in blood. It was not unusual for some families to take their children back to see their places of birth. This was never a topic in my family. Later in her life when in the hospital after a fall and a hip replacement, she made my husband promise never to go to Poland. When the opportunity came up for me to join a tour of Poland with a group of Holocaust educators, I agreed to go without hesitation. After all, my mother never made me promise.

Since this tour was organized for Holocaust educators, the focus was not on the history of the Holocaust exclusively. The tour guide enriched his narrative with less-known historical facts and the compelling reality of the Nazi reign of terror. The educators were visiting these sites, for the first time, after teaching about them in classrooms around the country for many years. I fit into the group because I also know the history of the Holocaust, not as a historian, but as a child of survivors who read every book and watched every film that I could get my hands on.

In my professional life I am a psychologist and marriage and family therapist at the Council for Relationships. I have been involved in post-graduate training in marriage and family therapy at the Council for over 30 years. I also direct the Transcending Trauma Project, founded in 1991. Under the auspices of this project, 300 life history interviews with Holocaust survivors, their children, and grandchildren were conducted in order to study coping and adaptation after extreme trauma. I have listened to hundreds of testimonies documenting the impact of the Holocaust and the struggle to rebuild life after the devastation.

One of many pictures taken by the Nazis which comprises The Auschwitz Album. This picture is of arriving Jews standing in front of the railroad cars, awaiting the Germans’ orders.

They looked human suffering in the face and snapped the shutter of their cameras.

At the museum in the Auschwitz extermination camp, there were rooms with pictures of the victims taken by Nazi photographers to document the slaughter. These pictures are contained in the book called The Auschwitz Album. I knew these pictures before going to Auschwitz, I know the stories. I know the human suffering. I know what happened. Due to my role in the Transcending Trauma Project, I know the psychosocial factors of survivorship. But I must say that the eyewitness photographs were devastating – knowing is not a protection from the emotional impact. Seeing the terror in the victims’ eyes cannot but touch your heart. The other dramatic level of impact is the recognition that professional photographers, human beings, took these pictures that documented the Final Solution. They looked human suffering in the face and snapped the shutter of their cameras.

Even though survivors raised me, come from a family of survivors, and have witnessed the testimonies of countless others, it is still shocking. As I have questioned my entire life, I wondered again how could they have possibly survived and rebuilt their lives. I ask this question even though I am the evidence of survivors’ will to survive and rebuild.

As a child I would sit in darkness, cry, and wonder, how does one survive such devastation? I would wonder how do I go on with life knowing that such horror and destruction, perpetrated by human beings against human beings could have possibly happened. This question seemed unanswerable. Eventually, I sorted it out and settled upon one answer – the only important thing in life is people, and that made life worth it. I am the child of survivors asking this question. Can you imagine how survivors must have asked themselves the same question walking out of the gates of every concentration camp in Europe?

Father Patrick Desbois (pictured here) is a French Roman Catholic priest and the founder of the Yahad-In Unum, an organization dedicated to locating the sites of mass graves of Jewish victims of the Nazi mobile-killing units in the former Soviet Union.

How could this be?

So there I was in Poland, a beautiful country. Before I left, my Polish friend showed me beautiful pictures of her country and she wanted me to go to these special places. But the group was there for one week and other than riding on the bus going through the countryside, the only places that we went to see were Holocaust sites.

Through my work on the Transcending Trauma Project, I have come to know a great deal about survivorship. But how can anyone know about suffering who has not experienced it firsthand? When standing on the grounds of the death camps, there is no other possible response other than abject, paralyzing silence.

Not being a Holocaust historian, there were many facts that were brought home to me with great emotional power during the weeklong tour. I have always known that for the mass killings of Jews who were thrown into mass graves, the Nazis enlisted the service of the local population. This service was not forced or due to threats. Men volunteered and they were given guns with the directive to kill those lined up, naked and helpless, with one bullet per person. After all there was a shortage of bullets so conservation was essential. Many men, women, children, and babies fell into the mass graves shot but still alive, only to die of suffocation after extended suffering. Who were these men? Father Patrick Debois, a Catholic priest, has traveled through Europe searching for these unmarked mass graves in order to memorialize those who were murdered. He would interview the townspeople only to learn that many of them witnessed, as children, the mass killings. It was an afterschool activity. How could this be?

The Jewish population of Lodz, Poland (pictured here) was persecuted by the Nazis and forced into a walled-off zone called the Łódź Ghetto before being sent to concentration camps.

So they killed them.

Near the town of Tarnov, Poland, we walked into the woods to the site of a mass grave of 800 children. The children were taken from their parents and marched to the outskirts of the town and shot, one bullet per child, and fell into the massive holes dug in the ground. Then the grave was quickly filled in, and teenage children of the townspeople were brought out to the grave to stomp down the earth over the bodies so that the ground was even. And then the children went back to their homes. It was wartime and Poland was occupied by Germany. I cannot imagine the anguish of those parents who lost their children that day. I do not know the pressures on the families of these teenagers. How does one live with the memory of stomping on the mass grave of children?

The tour guide told us another story that was unfortunately not an isolated incident in war-torn Europe. He was in a town with another group and they spoke to a man living there with his family. After they parted ways, a woman walking down the block told him that the man they had been speaking to had killed two children left in the house after the deportation of the children’s parents. He buried them in the backyard and moved his family into the house. How can this be understood?

One more story, a personal story this time: After the war, my mother was with her few remaining relatives living in the town of Lodz, Poland. She returned to her hometown in Demblin, Poland, to retrieve fabric from her family home that her father hid in the walls and rafters for the family when they returned. A family was living in my mother’s former home and the woman let her in. She found the fabric but couldn’t carry it alone so she said she would return the next day. That night she stayed in a hostel that was set up for refugees left homeless after the war. In the middle of the night, the women were awakened by a group of men with guns who roused them from sleep and ordered them to line up outside the hostel. My mother was among them. They were shot down by these young men who were part of the Polish Nationalist Army, a right-wing nationalist group. Before being shot my mother recognized one of the men as a classmate from school. She was the only woman in the group of 25 who survived. She pretended to be dead and then crawled across a field to a farmhouse where the family got in touch with the authorities who took her to the local hospital. There were those in her hometown that did not want the Jews to return – so they killed them.

My struggle during this trip was trying to understand the perpetrators; the Nazis, the SS, the camp commandants, the guards, and the men who put the Zyklon gas into the gas chambers. I was tortured by the struggle to understand the teenagers who walked on the grave, the man who killed the children in the house, and the man who shot my mother after the war was over. Anti-semitism is the easy answer – although such hatred is beyond my comprehension. As far as I know, there is no psychological theory that explains the cruelty manifested by the average person.

The Transcending Trauma Project’s thousands of hours of interviews with Holocaust survivors and their families are held at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (pictured here) in Washington D.C. and at the Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum in Jerusalem.

Having been swallowed by darkness.

After returning from Poland, my Polish friend was very disappointed to know that I did not see any of Poland’s beauty. On the other hand, I didn’t have to face my mother, although I think that in the end, she would have supported this trip. But my mind keeps going over the question about the average person. Can this happen in the United States? Can my neighbor take over my home and kill my children if I were to be dragged away? Would a classmate ever hold a gun on me? That of course begs the question of whether or not I would ever be capable of such violence and cruelty myself. My answer is, of course, it would be incomprehensible.

I do not know why ordinary people do horrible things. But I do know that we ordinary human beings must be vigilant about our humanity. We can never take our humanity for granted. We must work on our sensitivity to others, and the value systems that guide us toward responsible action toward all people. We need to be aware of our unintentional prejudices, inadvertent slights, and failures in our commitment to the equality of all human beings. This is every day and in every circumstance, from the smallest of interactions to public engagement with all people. I also believe all of you reading this piece agree with me. But what about the others?

As the Director of the Transcending Trauma Project, I have been privileged to bear witness to the life histories of 300 Holocaust survivors, their children, and grandchildren. The Transcending Trauma Project team of interviewers asked the survivors how they were able to rebuild their lives. We have hours of testimony and descriptions of lives before and after the war. We have conducted interviews that explored not just what happened to survivors, but what they experienced inside – their thoughts, feelings, and beliefs – from the deepest despair to the kernels of hope – from feeling that one’s survival was a miracle to feeling that God turned away.

We have 1,200 hours of testimony. These interviews are unique precisely because they do not chronicle historical events – they tell the story of how survival is possible and how life can be affirmed after all is lost and everything one believes is shattered. There is so much to learn about life lessons from survivors – having been swallowed by darkness – each painful step forward is an attempt to hold on and live. It is striking that many survivors expressed their belief that to go through life with hateful feelings, angry attitudes, and hostile acts would mean that they were like their persecutors – that they would then be as bad as the Nazis.

Survivors stated that living a meaningful and good life was the ultimate victory against Hitler. They also valued carrying forth the legacy of their murdered parents and family members. Do not think this was easy – for many survivors, the pain has been a constant reality of life – but, to live meant to live as full a life as possible valuing the lives of others and carrying on with self-respect, dignity, and the strongest of commitments to their families. I do not believe that we have to face raw evil to affirm life – we just need to look into the eyes of suffering with an open heart.

Elie Wiesel (pictured here) is an author and Holocaust survivor who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986 for speaking out against violence, repression, and racism.

We must never fall silent.

During my time in Poland, Elie Wiesel died on July 2, 2016. Hearing the news I felt compelled to watch the international news channels, watching repeating documentary footage of the Holocaust focusing on the death camp Auschwitz, where Eli Wiesel and his father were imprisoned during the war. We were just at Auschwitz – it felt surreal. Elie Wiesel, perhaps one of the most famous Holocaust survivors in the world, author of the iconic book Night, won the Nobel Peace Prize in December 1986. He has been a tireless advocate for the people of the world to pay head to human suffering and to protest against injustice and persecution. Here is an excerpt from his acceptance speech:

“I swore never to be silent whenever and wherever human beings endure suffering and humiliation. We must always take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormenter, never the tormented. Sometimes we must interfere. When human lives are endangered when human dignity is in jeopardy, national borders and sensitivities become irrelevant. Wherever men or women are persecuted because of their race, religion or political views, that place must – at this moment – become the center of the universe”

I am the child of Holocaust survivors. Their suffering taught me to be vigilant about human suffering. With this mission, I have directed the Transcending Trauma Project – the study of survivorship and overcoming trauma. It is my fervent hope that this work with help mental health professionals and others assist those who have suffered as part of a group or as individuals.

We also have to be vigilant about our humanity. To never become complacent and to never be a tool of the persecutor. We must stay true to our moral standards and as Elie Wiesel said – we must never fall silent.

Bea Hollander-Goldfein, PhD, LMFT (pictured here) is a Co-Director of CFR’s Transcending Trauma Project and a Staff Therapist.

About the Author

Bea Hollander-Goldfein, PhD, LMFT is a Co-Director of CFR’s Transcending Trauma Project and a Staff Therapist. Dr. Hollander-Goldfein has also authored numerous books, including Transcending Trauma: Survival, Resilience, and Clinical Implications in Survivor Families. If you have questions for Dr. Hollander-Goldfein about her trip to Poland to better understand the trauma caused by the Holocaust, or if you would like to schedule an appointment with her, you may reach her at bhollander@councilforrelationships.org or 215-382-6680 ext. 3118.

If you are looking for individual, couple, or family therapy or psychiatry, click here to request an appointment. See our Therapist & Psychiatrist Directory to find additional CFR therapists or psychiatrists near you.

About the Transcending Trauma Project

The Transcending Trauma Project has produced 1,200 hours of in-depth life history interviews which have been preserved as digital archived files. The Phil Wachs and Juliet Spitzer Archive of the Transcending Trauma Project are housed at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum and the Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum in Israel.